It starts off innocently enough – a runny nose, a mild fever, maybe a cough. But then comes the telltale rash, spreading like a polka-dotted rebellion across the skin. Measles might sound like a disease from the history books, but it’s staging a major comeback, even as most of us fervently wish it had stayed buried in the pages of outdated medical journals.

So, What Is Measles?

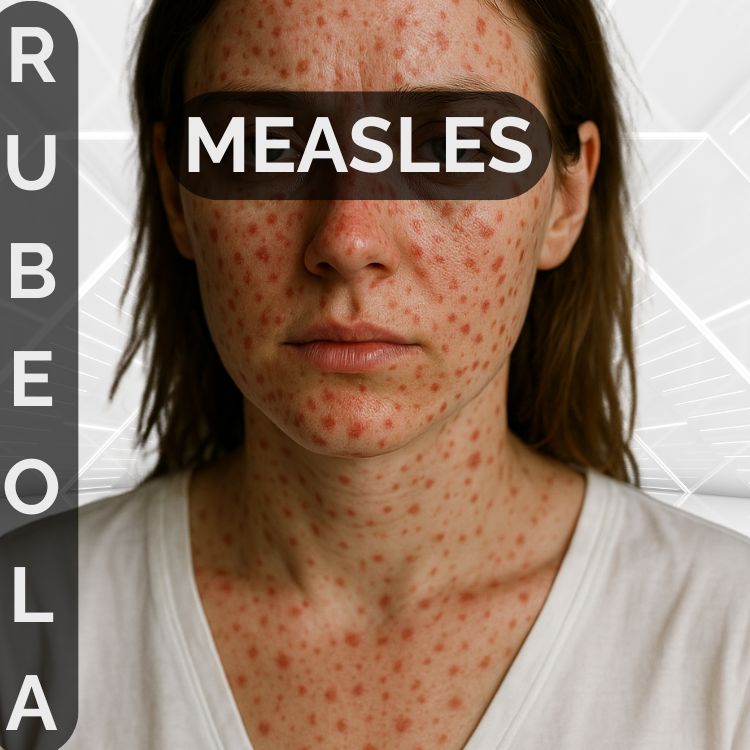

Measles is more than just a rash—it’s a highly contagious viral illness that used to be a nearly universal childhood experience. Caused by the morbillivirus, it spreads through droplets in the air when someone coughs or sneezes. Think of it as the overachiever of contagious diseases: if someone with measles walks into a room and leaves, the virus can hang in the air for up to two hours, just waiting for its next host. If you’re unvaccinated and nearby, there’s a 90% chance you’ll catch it. That is not a typo! Ninety!

Symptoms include:

- High fever

- Cough, runny nose, red eyes

- Koplik spots (tiny white spots inside the mouth)

- A signature red, blotchy rash starting on the face and spreading downward

It’s not just a “kids’ illness”—measles can lead to serious complications, including pneumonia (a type of lung infection), encephalitis (brain swelling), and death, especially in children under 5 and adults over 20.

How does it start?

It starts with flu-like symptoms—fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes. Then, just when you think it couldn’t possibly get any worse, the infamous red rash makes its appearance, beginning at the hairline and working its way down like a blotchy, itchy curtain call.

Why Does Your Grandma Probably Remember It So Vividly?

Because before the vaccine, almost everyone got it! Measles was a rite of passage in the same way chickenpox was for millennials – only far more dangerous. Your grandma might recall being confined to a dark room (to soothe the light sensitivity), bathed in calamine lotion, or having siblings take turns falling ill like dominoes. Entire neighborhoods would go under a kind of unofficial quarantine.

But it wasn’t just uncomfortable—it was deadly. Before 1963, millions of cases occurred every year, and hundreds of children died annually in the U.S. alone. The sound of measles wasn’t just coughing—it was the silence left by empty cribs.

Why Do Modern Moms (Especially Those Expecting!) Need to Pay Attention?

Because despite modern medicine’s best efforts, measles is back – with a vengeance! Fueled by declining vaccination rates in some communities and the ease of global travel, this once-contained virus is staging a dramatic return. Outbreaks are popping up in schools, airports, and even hospitals—places that should be safe.

And measles isn’t just “one of those childhood illnesses.” It’s out to remind us of its power. This virus doesn’t just bring a rash and a fever; it can lead to pneumonia, brain inflammation, permanent hearing loss, or even death—sometimes in children who were otherwise perfectly healthy.

For pregnant women, it’s especially serious. Measles in pregnancy can lead to miscarriage, premature birth, and low birth weight. And here’s the kicker—pregnant women can’t get the MMR vaccine, since it’s a live-virus vaccine. That means ideally, you need immunity before you conceive.

So, whether you’re a parent, a soon-to-be grandparent, or someone with travel plans, measles deserves a spot on your radar—not to scare you, but to remind us all how lucky we are to live in an era where prevention is just one shot away.

A Story from the Pre-Vaccine Era: “The Summer of the Spots”

They still talk about it, in old Chicago neighborhoods where screen doors slam and porches lean with age—the summer of ’53, when the measles came knocking.

I once read the account of a woman named Alice, who was nine years old that summer. She remembered it not by dates or headlines, but by the color of the curtains—heavy, dark ones her mother hung over every window to ease the stabbing light that hurt her eyes. She remembered the itch, the fever, and the way the laughter on her street fell silent almost overnight.

It began with a boy named Danny, two doors down. He was the fastest kid on the block and could slurp a popsicle in one breath. One day, he stopped coming outside. Then his sister. Then the kids across the street. Within a week, the whole neighborhood was under an unspoken lockdown. Mothers passed calamine lotion and whispered updates over fences like secrets. The air was thick with the smell of vinegar baths, boiled linens, and fear.

Alice wrote about lying in bed, sweat-drenched, with a damp cloth on her forehead and the sound of her mother crying softly in the kitchen. She wasn’t crying because Alice was sick—she was crying because Clara, the curly-haired girl from down the block, wasn’t getting better.

Clara didn’t come back out that summer. Her front steps stayed empty. Her jump rope, abandoned in the grass, became a symbol of the summer’s shadow.

Alice survived. But she never forgot. “Measles wasn’t just a rash,” she wrote. “It was the ghost that passed through our neighborhood, knocking on every door. And for some, it stayed.”

The Game-Changer: A Vaccine Is Born

Fast forward to 1963. Rotary phones still hummed on kitchen walls, and the world was looking to the stars, with space exploration capturing global attention. That same year, something equally groundbreaking happened here on Earth: the first licensed measles vaccine was introduced in the United States, marking a turning point in public health.

Though many scientists contributed to the development of the measles vaccine, the work of Dr. John Enders—a Harvard-trained physician and microbiologist—was central. Already a Nobel Prize winner for his groundbreaking work in cultivating the polio virus, Enders turned his attention to measles, a disease so common that, by the early 1960s, nearly every child contracted it by age 15.

Thanks to his team’s meticulous research and the eventual rollout of the vaccine, the tide began to turn.

In 1968, an improved version of the measles vaccine—developed by the prolific Dr. Maurice Hilleman, who created over 40 vaccines in his lifetime—became the new standard. Just a few years later, in 1971, it was combined with the mumps and rubella vaccines to form the now-familiar MMR vaccine, simplifying childhood immunization and dramatically reducing disease rates worldwide.

In 1989, the United States adopted a routine two-dose MMR vaccine schedule after outbreaks revealed that one dose didn’t provide lifelong immunity for all children. The results were dramatic: measles cases dropped by more than 99% compared to the pre-vaccine era! Hospitals that once braced for waves of pediatric patients with high fever, rash, and dangerous complications began to enjoy a new calm. Where measles had once raged, silence reigned.

In fact, in 2000, the CDC declared measles “eliminated” from the United States—meaning there had been no continuous transmission of the virus for over 12 months. It was a public health triumph, made possible not by a miracle drug, but by science, collaboration, and a little needle with a big impact.

🧠 Sidebar: Elimination vs. Eradication

Elimination

✅ Means a disease is no longer spreading within a specific geographic area for at least 12 consecutive months.

🗺 Example: The U.S. eliminated measles in 2000, but cases can still be imported from other countries.

Eradication

🌍 Means the disease has been completely wiped out worldwide, with no new cases anywhere.

✔️ Only one human disease has ever been eradicated: smallpox (declared eradicated in 1980).

Why it matters:

Even after elimination, a disease like measles can return if enough people remain unvaccinated—because unfortunately, viruses don’t need passports.

So, Why Are We Talking About It … Again?

Because it’s back. In recent years, outbreaks have surged worldwide, including in the U.S., largely due to vaccine hesitancy and global travel. In 2024, over 40 U.S. states reported cases. Unvaccinated communities act like dry brush for a spark.

It’s more than an inconvenience. In low-resource countries, measles still kills over 100,000 people a year.

Measles and Pregnancy: A Dangerous Mix

Pregnant women who contract measles face significantly increased risks of miscarriage, preterm labor, low birth weight, and stillbirth. It’s more than a rash – it can be a real threat to both mother and baby.

Because the MMR vaccine is a live virus vaccine, it is contraindicated during pregnancy. That makes pre-pregnancy immunity crucial. If you’re planning to conceive and don’t know your MMR status, a simple blood test can check your immunity. If you’re not immune, you can get vaccinated—but you’ll need to wait at least four weeks before trying to get pregnant.

As an OB/GYN, I’ve had to deliver difficult news when a pregnant patient was exposed to measles. It’s not theoretical-measles carries real consequences, especially when life is just beginning.

Wait! Was Anyone Famous Ever Affected?

Absolutely. Measles has touched many lives—including those of the famous and fictional.

Queen Elizabeth I suffered a near-fatal bout of smallpox in 1562, which left her with facial scars. To conceal these, she adopted her iconic white lead-based makeup, a practice that may have contributed to her declining health later in life.

In literature, Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women references measles as a common childhood illness. In Chapter 9, titled “Meg Goes to Vanity Fair”, Meg March expresses her delight at an unexpected opportunity:

“I do think it was the most fortunate thing in the world that those children should have the measles just now,” said Meg, one April day, as she stood packing the ‘go abroady’ trunk in her room, surrounded by her sisters.

This line refers to the King children, for whom Meg works as a governess, contracting measles. Their illness frees Meg from her duties, allowing her to accept an invitation to stay with her friend Annie Moffat for two weeks. This scenario illustrates how common childhood illnesses like measles were during the 19th century, often influencing daily life and social plans. Alcott’s inclusion of measles in the narrative reflects the reality of the time, when such illnesses were prevalent and could disrupt routines. The casual mention underscores how these diseases were woven into the fabric of everyday life, affecting decisions and opportunities.

So Where Do We Go From Here?

Back to science. Back to public health. Back to compassion.

Vaccines aren’t just about “your kid.” They’re about everyone—from the newborn too young for their first dose, to the pregnant woman who can’t be vaccinated.

Final Thoughts: A Dose of Perspective

We live in a time when one tiny injection can prevent a potentially deadly disease. That’s not fearmongering—it’s progress. And it’s a gift.

So here’s to good health, strong science, and a world where the only spots we worry about are those on a ladybug’s back.

“If we had just one vaccine for every major disease as effective as measles, we’d be done with most infectious diseases in the world.”